#45

[A555] MICHAEL KAPROV’S FAMILY:

CAPITALIST,

WAR HERO, AND POGROM

by [A558] Gene Katzman

Editor’s note:

[A552] Shemariah Kaprov was the fifth of [A290] Khaim Kaprove’s eight

children. Virtually nothing was known about the branch until we heard from

cousin [A558] Gene Katzman. In the early 1900s, this branch had become

prominent “capitalists” trading in horses. Some were war heroes, but all but

few died in the pogroms, and of the survivors, only a few survived the Nazis.

Their stories are below.

One member, [A556] Anna Kaprove, survived by sheer good

fortune (See Chapter #105). Chapter 106

tells of her descendants leaving Russia in the late 1980s when the Soviet

government officially again allowed Jews to emigrate. Cousin [A558] Gene

Katzman recounts the stories told to him by cousins [A568] Anna (nee Kaprove)

and [A567] Yakov Berdichevsky.

Fig. 45-1: [A553] Yakov Kaprov

family tree

[A553] Yakov Kaprov (1860-1921) was one of the most

important (if not the biggest) horse traders in Podolia, near [C13] Kiev, and

one of the wealthiest families in [C02] the Sokolivka/ Justingrad village of the

1,000 Jewish families living there.

From about 1890 to shortly after 1910 and the beginning of

WWI, Yakov would travel annually to Russia proper, which was unusual, for Jews

were rarely allowed to move beyond the borders of the Pale. He first went to Tsaritzyn,84

which was the railroad terminus and biggest port on the banks of Volga River.

From there, he would travel about 800 miles to the east, and what is today’s

Kazakhstan. There in the prairie country, Yakov would purchase horses in the

hundreds. He would hire the necessary people to help him herd the horses back

to Tsaritsyn (Volgograd), where he would then have them loaded, having hired

the entirety of the whole railroad train. The train went to [C36] Uman, the

principal city some 30 miles south of Sokolivka. The Russian military itself

was, in all likelihood, the primary purchaser of the horses. However, once World War I began, the

military’s need for horses jumped, and undoubtedly, the Russian Army appropriated

most if not all of Yakov’s horses and his horse business ended. It is unknown

in what other companies Yakov had interests.

By 1914, Yakov’s oldest son, [A554] Samuel, had left for

the United States. Once settled in Philadelphia, he changed his last name to

Kaplan.

Yakov’s second son, [A555] Michael, was drafted into

military service when he was 17 years of age.

He was stationed in the region of Brody, an area about 40 miles

northeast of Lvov and for some time near the Russia/Austro-Hungarian border. During

a significant event in World War I, the nature of which remains unknown, he was

awarded a highlevel medal available to non-commissioned officers. Typically, it

would have been the Georgian Cross, but only Christians were allowed to receive

it.

A more chilling event occurred during this time. Michael

was at the Brody front when something took his attention. He heard a whispering

Hebrew prayer or a cry for help in Yiddish. None of his companions knew

Yiddish, and so had no idea that the enemy troops had Jews in their ranks. In

the dark without any of his compatriots knowing, Michael returned to the area

only to find the wounded Austrian-Hungarian soldier who was a Hungarian Jew and

who had been left alone. As befits a good Jew, Michael helped the fellow Jew by

giving him the medical care available to him and provided him bread and other

food. He also led him back close to Austro-Hungarian trenches. He knew that had

he told any of his Russian compatriots of his actions, he, himself, would have

been killed.

Toward the end of the war, [A555] Michael married [A555a]

Leah Grinberg, who came from Pliskov, a small town in the Podolia / Kiev

Gubernia. Leah’s family was in the milling business and far better off than

most other Jews.

But their life was soon to be torn asunder. After living in

Pliskov for more than a year, and Leah giving birth to [A556] Anna, they came

to Sokolivka in 1919 in time to die in a pogrom.

![]()

84

Tsaritsen

(1589-1925) was an early industrial city of Russia. After World War I its name

changed to Stalingrad (1925 – 1961). The

Soviets' Battle of Stalingrad and the invading German Army was one of the most

bloody and largest battles in the history of warfare. Since 1961, the city’s

name has been Volgograd. The city lies on the Volga River's Western bank and is

a major administrative center. It is strategically located close to the Don

River.

World War I had ended, but the civil war was beginning in

Russia, which ultimately led to the formation of the Soviet Union. During this

interregnum, would-be military leaders (a.k.a. Bandits) came and went, often

monthly. The worst were [A284] Zeleny and [A286] Petliura (See chapter #54).

The one theme all non-Jews shared, and that included many of the non-Jewish

neighbors, was: “Everybody hates the Jews.”

Michael Kaprov quickly became a leader of the Jewish

Self-Defense Group in Sokolivka/ Justingrad.

And then came the infamous pogrom of August 1919, where

Zeleny demanded 1,000,000 rubles, the sum of which was impossible to raise.

Zeleny rounded up about 240 men and locked them in a house. Finally, 200,000

rubles were raised, but still, it was not enough. In retribution, ten men were

murdered. Michael was one. When more money could not be raised, Zeleny killed

another ten. Finally, he and his men went to various homes, killing and

burglarizing at will.

Fig. 45-2: Grinberg-Kaprove family,

C1836 taken in Justingrad.

L-R Top: [A556] Anna Michalovna

Gilman (nee Kaprov), [A573] Chaya Kaprov, [A571] Belchik Kaprov;

Lower: Raizel Berdichevsky, [A568]

Anna Tokar (nee Berdichevsky), [A566] Ratsa Berdichevsky (nee Kaprov), [A566a]

Samuel Berdichevsky, [A567] Yakov Berdichevsky.

Fig. 45-3: Grinberg-Kaprove family,

1926 taken in Pliskov.

L-R Top: [A555a] Leah Kaprov (nee

Grinberg), Israel Grinberg, Basya Grinberg Ruvinsky; Middle: [A556] Anna Michalovna Gilman (born

Kaprov), Surah Chaya Greenberg, Laib Greenberg; Lower: Manya Greenberg.

Fig. 45-4: [A566] Ratsa Kaprov and

son [A567] Yakov Berdichevsky.

Fig. 45-5: Tokar family: [A568a]

Boris, [A570] Leonid, [A570a] Marina, [A568] Anna, and [A569] Aleksandra (1985

in Belaya Tserkov).

[A553] Yakov, [A553a] Hannah, and several tried to hide in

a crawl space beneath the home but were discovered. The problem when hiding was

how to quiet the small children. To silence those who began to cry, the parents

would stuff pillows into their mouths.

[A567] Velvel, who was then about 17 years of age, along

with about 100 other youngsters, were taken to a nearby ravine. All were

murdered when no money was forthcoming.

By the end of the pogroms, [A555] Michael and others in the

family had died (See

Appendix D). [A554] Yakov, [A554a] Hannah, [A555a]

Leah,[A556] Anna, and [A566] Ratsa survived. Leah, with Anna, had returned to

her parents and siblings in Pliskov.

Yakov and Hannah could not bear the death of their two sons

and soon also passed away. Ratsa and Belchik (who was then in Odessa) were the

only two people who survived from what was once the prosperous and happy

mishpocha that was called the Kaprov family.

Soon Ratsa and Samuel Berdichevsky married and moved to

[C43] Zashkov to his family. Zashkov, a small town in Cherkasy Oblast, is the

center of Zashkov district, located 10 miles north of Sokolivka. The first of

their two children, born in 1928, was named to honor her grandfather [A553]

Yakov. [A568] Anna, born two years later, was named to honor her grandmother

[A553a] Hannah Kaprov. Samuel’s father had built the home several decades

earlier.

[A571] Belchik graduated from one of the Odessa

universities with an engineering degree in making brad equipment. He married

[A571a] Chaya, who was Jewish and grown up in the local community. In 1937,

another [A572] Yakov entered the family. He was a full namesake to his

grandfather [A553] Yakov Kaprov.

Despite the promising beginning, ugliness followed. Someone

in Belchik’s company falsely accused him, and after a trial, he was imprisoned

for seven years in Siberia. Chaya and little Yasha (Yakov Kaprov) returned to

Zashkov to reside with the Berdichevsky family. In June 1941, the Nazis invaded

the western frontiers of the USSR, eventually pushing East. [A566a] Samuel was

drafted into the Red Army, dying in 1943 during the war. At the end of June,

Ratsa met a Sokolivkan Jewish neighbor, who, as a Red Army soldier retreating

through Zashkov, told her that as the Nazis come, the locals were clearing the

area for the Germans by rioting, burglarizing, and exterminating their Jewish

neighbors. Ratsa quickly ran home and let [A571] Chaya and Raizel Berdichevsky

(mother of Samuel Berdichevsky) know that they must leave immediately, and walk

East to leave Ukraine, and get to the Russian proper. Chaya and Raizel

refused.

With this new and alarming information, [A566] Ratsa, in

contrast to Chaya and Raizel, immediately took both of her children, [A567]

Yakov and [A568] Anna, and quickly left Zashkov, walking easterly. They covered

125 miles during the first month coming near Cherkasy. By chance, Ratsa saw a

horse, and being a horse trader’s daughter, knew well how to care for the

animals. Thus, during the second part of their journey, they rode rather than

walk. Soon they “rode” the next 200 miles to Kharkov where there was a train

station. By train, they soon were in Central Asia, and by October 1941, in

Samarkand, Uzbekistan, where they lived until early 1944 when Ukraine was Nazi

free.

Chaya and Raizal’s story ended tragically. The moment Nazis

entered Zashkov, the locals drove the Jewish families from their homes and

informing the German soldiers where to find the Jews. Some Ukrainians went

further. They, themselves, killed their Jewish neighbors. The local neighbor

who envied the house Samuel’s father built, came over, and killed both women

together, including the five-year-old, Yasha.

In 1944, when Ratsa with her children returned to Zashkov,

they found the neighbor with his big family occupying the house. He claimed the

house was his now, and “you Jews have the nerve to ask for it. You should be

happy you got your life. You do not know when to stop. And now you want the

house. What are you going to ask for next?” Ratsa left and found temporary

lodging before finding a permanent home several years later.

Yakov later graduated from school and moved to Kiev, where

he lived for some time before moving in 1973 to Israel. Ratsa joined him in

Israel a year letter. In the mid-fifties, Anna Berdichevsky married Boris Tokar

and moved to his town, Bila Tserkva, some 30 miles southwest of Kiev. In 1990,

with their two children, Aleksandra and Leonid, the family joined Yakov in

Israel. Ratsa died a half year before they arrived. Yakov, now 92 years old,

lives in Migdal-Haimek, located 3 km north of Afula, Israel.

Some good fortune ensued. Laib Grinberg (1875-1941), who

had become Greenberg, was [A555a] Leah’s father and Anna’s grandfather (not on

the Kaprov side); his other children later prospered. Israel Greenberg became a

well-known scientist specializing in physics. After having been admitted to a

prominent physics institute in Moscow and himself already now recognized as outstanding,

he led the other Greenbergs in the family to live in Moscow. [A556] Anna along

with [A555a] Leah, Basya, and Manya Greenberg, thus came to reside in Moscow.

Russia, from after the pogrom era, the revolution and

through the 1930s, became more

“friendly” to Jews, especially to those who were not openly

religious. During the 1930s, the

population of Jews in Moscow numbered more than 500,000, which was exceeded

only by New York City and Warsaw. Moscow had become a major Jewish center with

two important Jewish theaters, Hodima (Hebrew) and Goset (Yiddish), as well as

several Yiddish Schools and even several Synagogues. The Grand Choral Synagogue

of Moscow was the home of the main Rabbi of Russia and later of the Soviet

Union, which might be unique for the Atheist State. By 1939 Jews had become the

city’s principal ethnic group. The city’s population of Jews (400,000) was

second only to Russians.[1]

See Chapter #105, which recounts the most unfortunate

episode where grandfather Laib Greenberg (Grinberg), his wife Surah Chaya

Greenberg, and other relatives went to attend a funeral in Pliskov in Podolie,

just when on June 22, 1941 the Nazis invaded Russia during World War II. All were killed. Only Anna survived as she

had remained home preparing for exams at the Moscow Medical University.![]()

#106

[A556] ANNA MICHALOVNA KAPROVE, AFTER THE NAZIS by [A558] Gene Katzman

[A556] Anna Gilman (nee Kaprav), in the early summer of

1941, began medical school at the Moscow Medical University. Her beloved

grandfather, Leib Greenberg, had just passed away in the shtetl of Pliskov in

Podolia (central Ukraine). The entire family, including mother [A451.4a] Leah

Kaprov Grinberg, plus her aunts and uncles and many cousins living in Moscow,

came to pay last respect and take care of their Grandmother, Surrah Chaya

Greenberg, planning for her to return with them to Moscow. Anna had exams and

was unable to go. Unfortunately, two weeks later, the Nazis invaded the western

frontiers of the Soviet Union, where Pliskov happened to be (150 kilometers

from the Soviet/Romanian border.) The family, trapped in Ukraine, spent their

last days in the [C38] Vinnitsa Ghetto. They all perished in a fire the Nazis

began and kept sustained by local sympathizers of Hitler’s ideas. Thus, Anna

lost her entire family in a single moment. She had already lost her father,

[A555] Michal Kaprov. In one of the many pogroms when she was less than a year

old. Now, not yet quite 21, she was utterly alone in a horrible war-stricken

world.

By the summer’s end, she was drafted to the medical train division

as a war nurse. She spent the next four years (1941-45) on a medical train

traveling to the front line to pick up the wounded from the places of battle to

then transporting them to the rear where it was safer. The picture dated late

fall 1943 shows Anna on the lower row, to the extreme right. [A828a] Yelena Bonner,[2]

who later married physicist [A828] Andrei Sakharov,[3]

is in the center next to Anna. Yelena became a famous human rights advocate,

and her later husband became known as the “Father of the Russian hydrogen

bomb.” He later became a prominent

dissident.

For her work, Anna received the medal, “For the victory over

Germany in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945.”

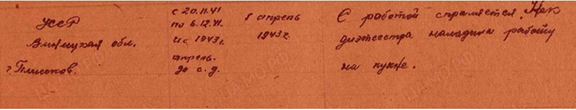

Kaprav Anna Mikhailovna

Award presentation

Rank: ml. lieutenant

Location: VSP 122

Record number: 1536453285

Fig. 105-1: Anna’s (Lower right,

front row) medical team. Center, front row, Yelena Bonner, future wife of

Andrew Sakharov, father of Russian hydrogen bomb and later dissident fighting

for human rights; Right: Medal “For the

victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945.” English:

#

Full Name Army Rank Occupation Birth

Yr Nationality

Education

9 Kaprav Anna

Mikhalovna Jr Lieutenant Registered

Nurse 1920 Jew

Med Student

Place

birth Yrs in Red Army

& current place Characteristics

Ukranian SSR 11/20/1941 04/08/1943 Meet the expectations, performs Vinnitsa

District

dual duties as a nurse and Pliskov

supervises kitchen.

Fig. 105-2 Documentation associated with the medal.

Fig 105-3 [A556] Anna Michakovna Kaprove and [A556a] Yosef Salomonovich Gilman 1951.

#107

GLASNOST AND COMING TO AMERICA by [A558] Gene Katzman

[A558] Gene (Gennady – birth name) Katzman was born in 1971

in Moscow. His parents, [A557] Elena and [A557a] Konstantin Aron Katzman, were

two years apart in age (father born 1948, mother born 1950), and both had met

when they were college students. In the USSR, each major city had a single

University and multiple institutes organized by specialty, such as printing,

engineering, law, medicine, etc. Both parents were at the Moscow Polygraphic

Institute, which focused on large-scale printing. Konstantin’s training dealt

more with the engineering associated with big operational, highly complex

printing systems. Elena trained in accounting and economics. Their schooling

programs were five years long, and their degrees would be equivalent to a

master’s degree that one might receive today.

Gene was about five years old when he first learned about

antisemitism.

He lived near his grandparents, at Sokolniki, a

neighborhood on the northeast side of Moscow. Their home was in an apartment

complex where the typical buildings were uniform and five-six stories high.

Children from all areas would play together. There were no computers back in

the 1970s with which to play. Kids then would all hang out together for the

day. Homework from school would be completed, allowing the children to resume

play in the common area.

Their neighborhood was largely made up of children of

Russian background. His playmate, who was also about the same age, would call

out “Yid, Yid” to describe another child who might look slightly different.

Gene then did the same when he came home. Gene’s father asked him if he knew

what “Yid” meant, to which he had to say he did not. His father then told him

that the word meant Jewish and that he, Gene, was Jewish, his father was

Jewish, his mother was Jewish, his grandparents were Jewish, and so were all

his uncles, aunts, and grandparents. They were all Jewish. Gene was surprised.

The next question that came out of his mouth was, “So Aunt Sopha (Sophia

Davidovich, cousin of Konstantin Katzman) is a Jew?” The answer was

affirmative. Gene had another question ready. Was her husband, Uncle Gene

(Davidovich), a Jew too? The rest looked

like a ping pong match. Gene was shouting the names of the relatives and

friends of the family and was getting the defiant “Yes” back. It probably would

last forever, until Gene asked the last question. “So Aunt Olga’s (Olga Sorokin

– Elena Katzman sister) dog “Boruch” is Jewish?” Konstantin smiled and answered, “Do you think

someone would name a dog like this if it wasn’t Jewish.”

Gene came to understand that calling someone a “Yid” was

done purposefully in a most derogatory manner. It was meant to be hurtful. It

was meant to mean that you were different than all others.

In school, Gene also learned that many of the facts about

your life were not anonymous. The teachers knew much more about you than you

might have believed. The classroom list of students included not just your

name, but your religion or ethnicity and where you lived. Nothing was hidden.

Even if the student or the parents did not wish for the teacher to know, all

knew that the teacher did know.

Another story from Gene’s childhood describes the child’s

reaction to the Anti-Jewish and Anti-Israeli atmosphere dominant in Moscow

during the early to mid-1980s. Gene attended the elementary school in the

Southern Yuzhnoe Izmailovo neighborhood on the East side of Moscow. He was in

third grade. In his class was another Jewish child whom Gene befriended, Valery

Yazmir (now living in Petach Tikva, Israel), who has remained a good friend.

These two Jewish kids in a class of gentiles started to fill their real

identity, and their sense of Jewish belonging grew exponentially. Both learned

the Hebrew alphabet through an old textbook found in Val’s grandfather’s

library. An after-school activity was to beautify the school building and

surrounding territory. They were given a job to paint a playground located in

the school vicinity. The paint was blue. After the job was completed, and some

paint was still available, the two wondered how they might utilize it as

intended. Gene suggested,

“See the Boiler Room Hut, just north of the school?”

“Yes,” replied Val.

“What if we paint ISRAEL in big Hebrew letters on a wall of

the Hut?”

“Yes. It is a good idea. Let’s write it in Hebrew so no one

will know what it is and will not bother to clean it up.”

The two eagerly start painting the letters, filling a true

sense of their Jewish pride. Val then suggested a second idea,

“Let’s paint an Israeli Flag and wave it on my

balcony.”

“But you live on the 14th floor. Who

would see it? I live on the 4th, and it easily could be seen from

the street, offered Gene.” “Good idea,” Val agreed.

The moment they came to Gene’s apartment, they found

pillowcases in a linen closet. With scissors, they cut a big white rectangle

from it. Then using a deep blue paint, they painted the flag of Israel as best

they could. They found a hair dryer in a bathroom by which to dry the painted

flag. Several hours later, they raised the flag of the Jewish State from their

4th-floor balcony so it would wave over Moscow, the Soviet capital.

Soon after that, Gene’s father, Konstantin, came home from work and noticed

immediately the Jewish star and stripes waving on his balcony. Konstantin came

up with a wise decision. Let’s lower the flag from the balcony and express our

Jewish pride inside the Jewish apartment. All three of them, with dignity and

pride, went to the balcony and had a lowering of the flag ceremony. Gene and

Val blew Hatikva through their lips. Val was given the honor to hold the flag

in his room.

Gene’s mother-in-law (Ina Feldstein (Starik)) told a story

when the entire family was traveling to the Caucusus (Georgia) on vacation. A

young college student on the train asked her where she was from since she

looked more Georgian or Armenian than Russian. The person was surprised when

she said Jewish. He asked why was she being so harsh on herself. “I just wanted

to know what is your ethnic background, and here you are, shouting you are

Jewish.”

[A567] Yacov lived in Kiev, where antisemitism was far more

pronounced than in Moscow or elsewhere in many other regions of Russia. Just

the surname name could make it easy to suspect a Jewish heritage. Berdichevsky

sounded Jewish; without question, Katzman signified Jewish. Yacov was one of

the first family members who determined to emigrate and was speaking about it

with Gene’s parents early in the 1970s when he decided to leave. By 1973,

Gene’s parents had already decided they, too, would emigrate.

Throughout Gene’s teenage years, people did not hide their

feelings towards Jews. If you felt Jewish and not particularly Russian, then

you were asked when you were going home (meaning to Israel). Even though one’s

parents, grandparents, and earlier ancestors had already lived in Russia for

over 200 years.

To emigrate was not easy. One needed an invitation, which

generally meant from a relative in Israel. Having a sponsor was mandatory.

Yacov, by 1973, had already collected all of the papers

about the family history that would be needed for the authorities. The

organization to which one applied in Moscow was named OVIR (Office of Visas and

Registrations). In 1978, Gene’s parents decided definitely to emigrate and

turned in their documents to try to obtain exit papers. It was not until over a

year later that the Russian officials announced that they had reviewed the

documents and that the family definitely could not leave the country.

And that is when the real difficulties began. The Russian

officials would ask, “How could you want to go? Because if you’re a real

Russian, no Russian would want to leave.” But if you did wish to leave, then

you were a traitor, because only traitors would leave. [A557a] Gene’s father at

that time held a relatively senior engineering position in the printing shop of

the Moscow Academy of Science. Still, since he intended to leave, it was felt

there would be no reason that he should be allowed to continue in the printing

Institute, and so was fired. [A557] Elena, too, was deemed unworthy to hold her

job, as she too had become a traitor, and she was let go. To complicate this

period, grandmother [A556] Anna had developed cancer.

For the next year, life was most difficult as both parents

could only find the most menial jobs. Eventually, Elena got her old job back,

but not for Konstantin. Only after several years did he find a new more

substantial position, but with a different company.

Some of their relatives were also refuseniks.[4]

Gene Davidovich had had a Ph.D. in mathematics but was unable to find a job.

His wife (Sophia Davidovich), one of the first persons in the Soviet Union to

specialize in information technology (IT), lost her position and, for the next

decade, could only find a job as a mail carrier.

![]()

By the time Gene’s parents left in 1989, he was coming of

age and finally beginning to understand what antisemitism was, and all that was

happening. Friends got depressed when trying to leave. Starvation was to be

avoided, a difficulty without reasonable jobs. And the employers could be harsh

and would give any excuse conceivable except the real reason why good jobs and

promotions were so scarce. Being Jewish was an economic curse.

By the mid-1980s, many families had been refused permission

to emigrate, and their lives became exceedingly difficult subsequently. Gene’s

family just accepted that going would be difficult, but didn’t raise a fuss.

And that helped some; life was not as bad as it might have become.

In April 1987, their relatives, the Davidovich family,

announced they were leaving. Their son, Alex, was three months older than Gene.

By 1987 perestroika had begun.141At that time,

it was being said that only 6,000 people desired to leave, and since they were

all so vocal and making such trouble, it was thought, or so it was said, it was

just more straightforward to get rid of these dissenters and have quiet again.

Of course, the number that left during the coming years was about 2 million.

One piece of fortunate luck that helped Gene and his

parents was the visas they had procured earlier did not have an expiration time

limit. Thus, they were still active. During this period, acquaintances were no

longer friendly, but at least not overly hostile as before. The exit visas came

through. Gene’s family had choices. They had family in

![]()

141 Soviet

Pres. Mikhail Gorbachev, in 1990-1991 was the person single most important in

allowing

Russian Jews to emigrate. Leonid

Brezhnev, his predecessor (General Secretary, Soviet Union Communist Party,

1964-1982), began the practice of reforming the Russian economic and political

system in 1979. The changes truly came into full force when Soviet President

Mikhail Gorbachev promoted what was called “perestroika,” the policy permitting

greater awareness of economic markets, as well as ending central planning.

Perestroika lasted from 1985 until 1991. Its goal was to make socialism work

more efficiently. It was not to end the command economy. Gorbachev also

popularized “glasnost,” which meant "openness and transparency."

On December 5, 1965, a Glasnost

rally took place in Moscow, which was the key event leading to the emerging

Soviet civil rights movement. Specifically, early on, it allowed the public,

independent observers, and foreign journalists to attend trials in person.

Trials until then were closed to the public. As Chapter #105 relates. Andrei

Sakharov did not travel to Oslo to receive his Nobel Peace Prize as he was

publicly protesting about another political trial that was then occurring.

Gorbachev’s new policy or transparency now allowed the Soviet citizens to

discuss their system’s problems and potential solutions publicly.

Glasnost allowed greater contact between the Soviets and

Westerners and loosened restrictions on travel. Ultimately, this led to the policy

permitting Jews to emigrate to Israel and elsewhere. Reference https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Russia and https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/1991-03-01/glasnost-perestroika-and-antisemitism. For additional

material about later emigration, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1990s_post-Soviet_aliyah

Israel, and the Davidoviches, who were now already living

in Chicago, were willing to act as sponsors.

Of course, nothing was simple, especially in comparison to

today. The exit visa was for Israel. It could not be for the United States. But

at that time, the Soviets and Israel had no formal relations, which meant there

were no direct flights between the two countries. Everything had to be

conducted through third parties. And the moment Gene and his family left

Russia, their citizenships were declared null and void.

Using [A567] Yakov Berdichevsky’s name and address in

Israel for exit visa purposes, on April 6, 1989, the family flew to Vienna,

Austria. As with other families leaving Moscow and coming to Vienna, few had

their own family there. What had begun with just an occasional family departure

now was numbering at least 100 a day.

Fig. 106-1: Exit visa from Russia

and Entrance Visas to Austria for [A558] Gene, [A557a] Konstatin and [A560]

Sarah Katzman.

The arriving passengers quickly met inspectors where

officials from Israel were also present (Austria had diplomatic relations with

Israel). Unlike today’s airports where ramps led directly from the plane to the

terminal, the passengers had to walk down the stairways and across the tarmac

to the building where the Viennese officials met them. The Israeli immigration

officials, who were there also, quickly determined whether the passengers were

coming to Israel or did they wish to go to the United States or elsewhere. If

to the United States, the family was shunted to yet a different line and taken

to meet with officials from the “Joint” (Distribution). This meant meeting with

officials from HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), a Jewish-American nonprofit

organization operating since 1881 to provide humanitarian aid and assistance to

refugees, especially Jewish refugees. To this new family, it felt like they

were on a conveyor belt, but an exemplary conveyor belt at that.

Gene’s family stayed in Vienna for ten days and worked with

the US Embassy to claim refugee status. The Austrians were clear that they did

not want Russian Jews in the country, and so the stay was restricted to 10 days

and not more. Other non-Jewish groups, it seemed, were treated differently and

more generously.

From Vienna, the family left by train for a transit camp in

Ladispoli, a seaside village about 10 miles east of Rome.[5]

The family was given a small cottage, a monthly allowance, and a

Russian-Italian Dictionary. Heads of the families were told to start looking

for a place to stay elsewhere. The time given was a week due to the growing

wave of Russian Jewish emigration. The cottage needed to be readied for another

group of Jewish immigrates who left USSR the week later. Konstantin Katzman and

Peter Sorokin (husbands of Elena and Olga) were given a difficult task. Without

knowing the language, culture, and the topography of Italy, limited money

(Italian liras) and a small pocket-size Russian-Italian Dictionary, find a

place to live for their families during what proved to be a three-month stay in

Italy. On the last day of their stay at the camp, the men found the place at

Nettuno (Italian seashore countryside 45 miles south of Rome), which precluded

them from becoming the “Italian Homeless.”

All monies given for a monthly allowance suddenly had to be

used for monthly rent. The deposit to the landlord meant there was virtually

nothing left for day-to-day survival, food, etc. It was tough. The food stock gathered as an

emergency supply back in Moscow (instant soup cubes, canned meats, and fish)

was depleting rapidly. Families wanted to hide their survival needs, but it was

impossible to do so now. The local neighbors, who were simple Italian farmers,

helped to determine the needs of the new people in their village. They did not

ask if they needed help. Just one day, baskets of fruits and vegetables, as

well as freshly baked home bread, appeared on the footsteps of their front

door. They wanted to help but also wished not to harm their feelings. They

preferred their help to remain incognito. The family received nominal monies,

but as it was insufficient to live, the men who could work found illegal, relatively menial positions. The family

had come in April 1989 and left on July 13, 1989.

The children enjoyed the experience and the new location.

They liked living in a seaside village, and as it was summer, the beach was an

attraction. It was different for the

![]()

parents. Not only did they need jobs to support their

family, but they also had to prepare for interviews and obtain the necessary

papers for immigration to the United States.

Then came the interview at the US Embassy (Via Veneto,

Rome). Sophia Davidovich (cousin of Konstantin Katzman) provided a letter of

sponsorship to the HIAS Italian office. HIAS purchased the family’s airplane

tickets to Chicago. The Katzmans and Sorokins soon came to America on a

TWA Rome–New York–Chicago flight. At 9:10 p.m., the TWA plane landed in

O’Hare.

Once there, Gene’s father got a job as a technician in a

printing shop, and by August

1989, Gene’s mother began work as an accountant. After

another four months (March

1990), Elena secured a new job involved with payroll

accounting. She later became a COBOL developer and stayed in that line of work

for another 15-20 years until she retired. Gene’s father had difficulty moving

from his role as a technician to finding a job as an engineer. Also, the entire

printing industry was changing tremendously due to automation. Gene’s father

continued working for the rest of his career as a high-level technician.

In March 1991, Gene entered the University of Illinois at

Chicago and four years later graduated with Bachelor in Statistics Degree. But

his career in actuarial science did not happen to be. Gene found a job as a

computer programmer, later becoming a database system analyst. He now is a

Database Architect at the Wintrust Bank. In 2002, Gene received a master’s

degree in computer science at Keller Graduate School of Business. On June 1,

2001, Gene married Stella Leyzerova, also a Russian Jewish émigré who came to

Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1995 from Donetsk, Ukraine. Aaron Katzman was born in

2008 in Park Ridge, Illinois, 19 years after the Katzman family left the Soviet

Union.

[A560] Sarah Katzman, [A557a] Konstantin and [A557] Elena

Katzman’s daughter, came to the USA at age 14 years. She started in 9th

grade at Ida Crown Jewish Academy, and after the family moved to the suburbs,

she continued at the Main East High School in Des Plaines. The school is famous

for its students, Hollywood actor Harrison Ford and First Lady Hilary Clinton.

Sarah then went to the University of Illinois in Chicago and graduated from its

Information System program. Since 1997, she has worked as a computer system

analyst and developer.

Fig. 106-2: [A558a] Stella Katzman,

[A563] Anna Sorokin, [A562] Jane Sorokin, [A557] Elena Katzman, [A560] Sarah

Katzman, [A564] Lisa Sorokin, and [A561] Olga Sorokin (an aunt). 2011.

Fig. 106-3 [A558] Gene Katzman

family. [A558a] Stella, [A558] Gene, [A559] Aaron.

The [A561] Olga Sorokin (nee Gilman) family, [A557] Elena

Katzman’s younger sister, came to the US in 1989 together with the group.

Olga’s husband, [A561a] Peter Sorokin, was a medical doctor back in Moscow, and

taking series of medical exams and completing the residency, he continued his

medical career as a physician in one of the Chicago hospitals. Olga went into

public health by obtaining a research position in the College of Nursing at the

University of Illinois at Chicago. She worked there until retiring. Their

daughters, [A562] Eugenia (“Jane”), [A563] Anna (named in honor of her

grandmother), and [A564] Elizaveta (Lisa), attended the Solomon Schechter Day

Jewish Schools and Stevenson high school at Buffalo Grove. After graduating

from high school, Jane and Anna got their medical degrees at the University of

Michigan at Ann Arbor and the University of Wisconsin at Madison, respectively.

Jane practices obstetrics, and Anna, neurology. Lisa obtained her degree in art

and then worked in one of the art museums in Minneapolis, MN. All three have

families.

[1] In 1993, [A031b] Marion

Robboy’s cousin by marriage, Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt from in Zurich became

the Chief Rabbi of Moscow. In addition to being the spiritual leader of

Moscow’s central synagogue, he headed the Moscow Rabbinical Court for all of

the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

[2] Yelena Georgievna Bonner

(1923 – 2011), wife of physicist Andrei Zakharov, was a Russian human rights

activist. During her lifetime as a dissident, she was known for her great

courage and characteristic blunt honesty.

[3] Andrei Zakharov was the

father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb, but later opposed the Russian’s abuse of

power. In 1975, he was awarded the Peace Prize for his work for human rights.

Furiously, the Soviet leadership refused him permission to travel to Oslo.

Instead, Yelena Bonner received it on his behalf. Subsequently, Zakharov lost

all his Soviet honorary titles, and for several years the couple remained under

strict surveillance at their home in Gorki. In 1985, Gorbachev, now in power,

permitted them to return to Moscow.

[4] An unofficial term for

individuals, who typically were, but not always Soviet Jews, whom the Soviet

officials refused permission to emigrate, primarily to Israel.

[5] For Gene and his family,

this was heaven. But it was not always so for the Italians. Compromises had to be

made by all. See https://www.jta.org/2005/09/26/archive/first-person-a-camp-for-soviet-jewishrefugees-lives-on-but-only-in-peoples-memories,

https://www.jta.org/1989/04/11/archive/ladispolibulging-at-the-seams-as-soviet-jews-cram-seaside-town,

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-

02-19-mn-420-story.html,

and https://www.timesofisrael.com/why-189000-soviet-jews-fled-to-italy-rather-than-the-promised-land/.

No comments:

Post a Comment